Jamaica Rezoning Clears Council Committees, Promising 12,000 Homes and $413 Million in Upgrades

New York’s largest rezoning in two decades betokens a new approach to housing, infrastructure, and equity in the city’s often-overlooked southeast.

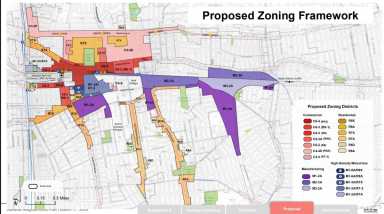

At a moment when the median rent for a one-bedroom in New York City nears a record $4,200, legislators in City Hall are rolling the dice on the single largest rezoning since the halcyon days of Bloomberg-era urban planning. On October 9th, the City Council’s Land Use Committee and its Zoning Subcommittee voted—unanimously, no less—to propel the so-called Jamaica Neighborhood Plan towards final approval. The measures would recast more than 300 blocks of southeastern Queens, a census tract long hemmed in by low-scale zoning and equally low economic expectations.

This plan is as ambitious as it is sprawling. It proposes nearly 12,000 new homes, of which a third—about 4,000—will be earmarked for permanent affordability. The remaking of Jamaica also envisages 2 million square feet of commercial space, much of it likely to sprout near the busy transit nexus at Archer Avenue. Buried in the fine print is perhaps the city’s most potent carrot: the largest Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) zone ever mapped, pushing privately-owned sites to yield nearly 3,800 affordable units.

Officials estimate the impact of this plan will unfurl over a leisurely fifteen years, a glacial pace by global megacity standards but positively brisk given the intricacies of New York’s review process. This scheme trundled through the City Planning Commission during the dog days of August with an 11-2 approval. Now, buoyed by the unanimous council votes, it seems on the cusp of crossing the last legislative hurdle.

For southeast Queens, where opportunity has too often felt rationed, the proposal portends much more than new towers or coffee shops. The $413 million in committed “community investments”—negotiated as the political price for upzoning—hints at a broader intent: to address Jamaica’s perennial flooding, tired infrastructure, and public spaces in disrepair. Funds will tackle the area’s creaky water and sewer systems, recurring stormwater nightmares, and the sort of pothole-pocked public realm that makes urban living feel more ordeal than adventure.

A particularly sharp focus falls on Archer Avenue. Today, it is, by the Council’s own phrase, “overrun” by illegally parked vehicles and cluttered by a bus terminal rendered dour by its aging canopy. The plan would devote nearly $18 million to conjure a new public plaza at Archer’s western flank—prone to the sort of inveterate loitering that afflicts under-cared-for interstitial city space—while another $47 million would bolster Station Plaza with public amenities and improved pedestrian safety. Even the bus terminals will get a $3 million artistic upgrade, presumably aimed at mollifying daily commuters and those merely waiting out the city’s legendary service delays.

Some New Yorkers may roll their eyes at the trickle of such “placemaking” investments, mindful of decades of unfulfilled promises and the city’s penchant for moving capital dollars across budget cycles with all the speed of a Staten Island ferry in heavy fog. That the Council also plans an independent oversight board for at least four years demonstrates, if nothing else, a hedging of bets.

First-order effects for the city are reasonably clear. The plan would inject a hefty supply of new dwellings at a time when skyrocketing rents and an anemic construction pipeline have turned even modest apartments into objets d’art. If all goes as forecast, Jamaica will enjoy not just new places to live but an economic infusion—7,000 jobs, according to DCP’s own estimates—ranging from retail to construction and all the specialised trades required to mend aging pipes and lay new infrastructure.

The second-order politics are perhaps even more telling. Advocates and city fathers often talk up the virtue of “community input,” but here the Council leveraged its role to demand investments up front—before the first foundation is even poured. It signals a new, transactional approach to rezoning: Gone are the days when density boosters could overrun local resistance with promises of “vibrancy.” In our view, such explicit quid pro quo bargains are likely to become the city’s new normal.

This approach also feeds the city’s broader struggle with housing equity. The plan’s requirement for permanent affordability—backed, crucially, by MIH rules—should nudge developers toward actually building the so-called “missing middle” units. If history is a guide, meeting affordability targets can prove elusive unless government puts its thumb on the scale. Neighboring districts looking on will note whether Jamaica’s new housing truly fits a range of incomes, or whether nimby tendencies manage to stymie the finer ambitions, as in other New York rezonings.

The city’s wager on density mirrors national trends—and exposes its own contradictions

New York, of course, is hardly alone in wrestling with the paradoxes of rezoning. From San Francisco’s recent headline-grabbing upzonings to London’s endless battles over the green belt, big cities everywhere are trying (and rarely succeeding) to balance housing, jobs, and liveability. Mayor Eric Adams’s administration casts the Jamaica plan as a harbinger of further reforms: Midtown, the Bronx, parts of Brooklyn—all are on the drawing board for similar treatment. Yet the city’s underlying housing math is stubborn. The Citizens Budget Commission notes that New York still operates at an annual deficit of roughly 40,000 below-market units. The Jamaica plan, while not puny by local standards, will not fill the chasm.

Economic worries also lurk in the wings. It remains to be seen whether a global interest rate environment unfriendly to developers, plus the city’s byzantine permitting regime, will allow this rezoning to actually spur as much private investment as anticipated. Construction costs are ballooning, tenancy laws remain tetchy, and even the promise of 7,000 new jobs must be weighed against long-term trends in retail automation and remote work—a reality for which scant provision is made in the plan itself.

None of this is to gainsay the potential for Jamaica to become, if not quite a new downtown, then at least a livelier hub for a borough long overshadowed by Manhattan and Brooklyn. The wry optimist in us notes that New York’s greatest physical transformations have always been accompanied by raucous debate about who benefits—and at what cost. If Jamaica can sidestep the pitfalls of previous rezonings, it may yet serve as a model for reluctant neighborhoods across the five boroughs.

The city is wise not to see rezoning as a solitary magic wand. Housing, jobs, and infrastructure need to march in lockstep for any measure of success. The next years will be the test, not just of Jamaica’s future, but of the city’s ability to build itself—prudently, patiently, and, for once, equitably. ■

Based on reporting from QNS; additional analysis and context by Borough Brief.